4 min read

It got better.

We spent months building a sophisticated internal text-to-SQL agent, d0, with specialized tools, heavy prompt engineering, and careful context management. It worked… kind of. But it was fragile, slow, and required constant maintenance.

So we tried something different. We deleted most of it and stripped the agent down to a single tool: execute arbitrary bash commands. We call this a file system agent. Claude gets direct access to your files and figures things out using grep, cat, and ls.

The agent got simpler and better at the same time. 100% success rate instead of 80%. Fewer steps, fewer tokens, faster responses. All by doing less.

Link to headingWhat is d0

If v0 is our AI for building UI, d0 is our AI for understanding data.

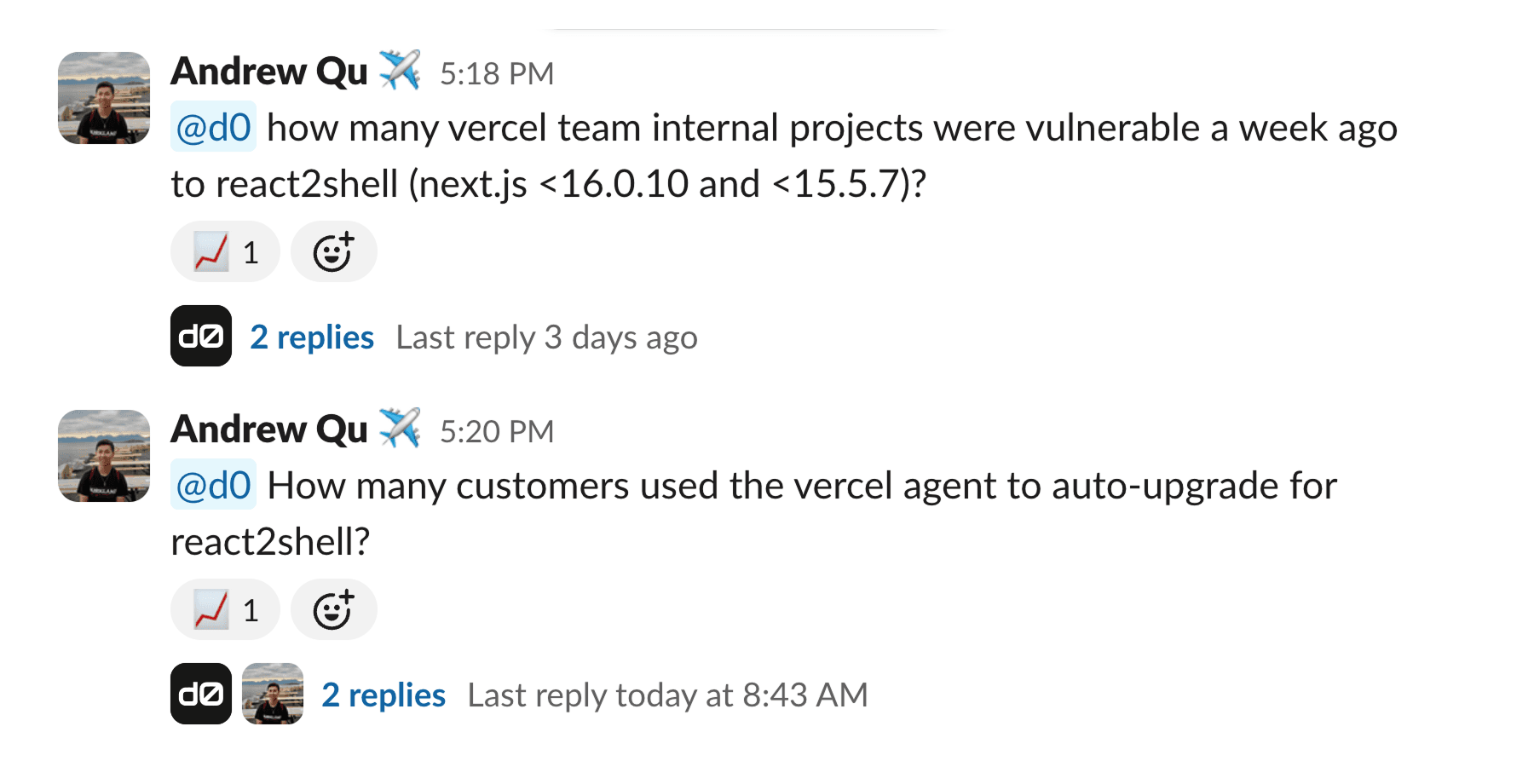

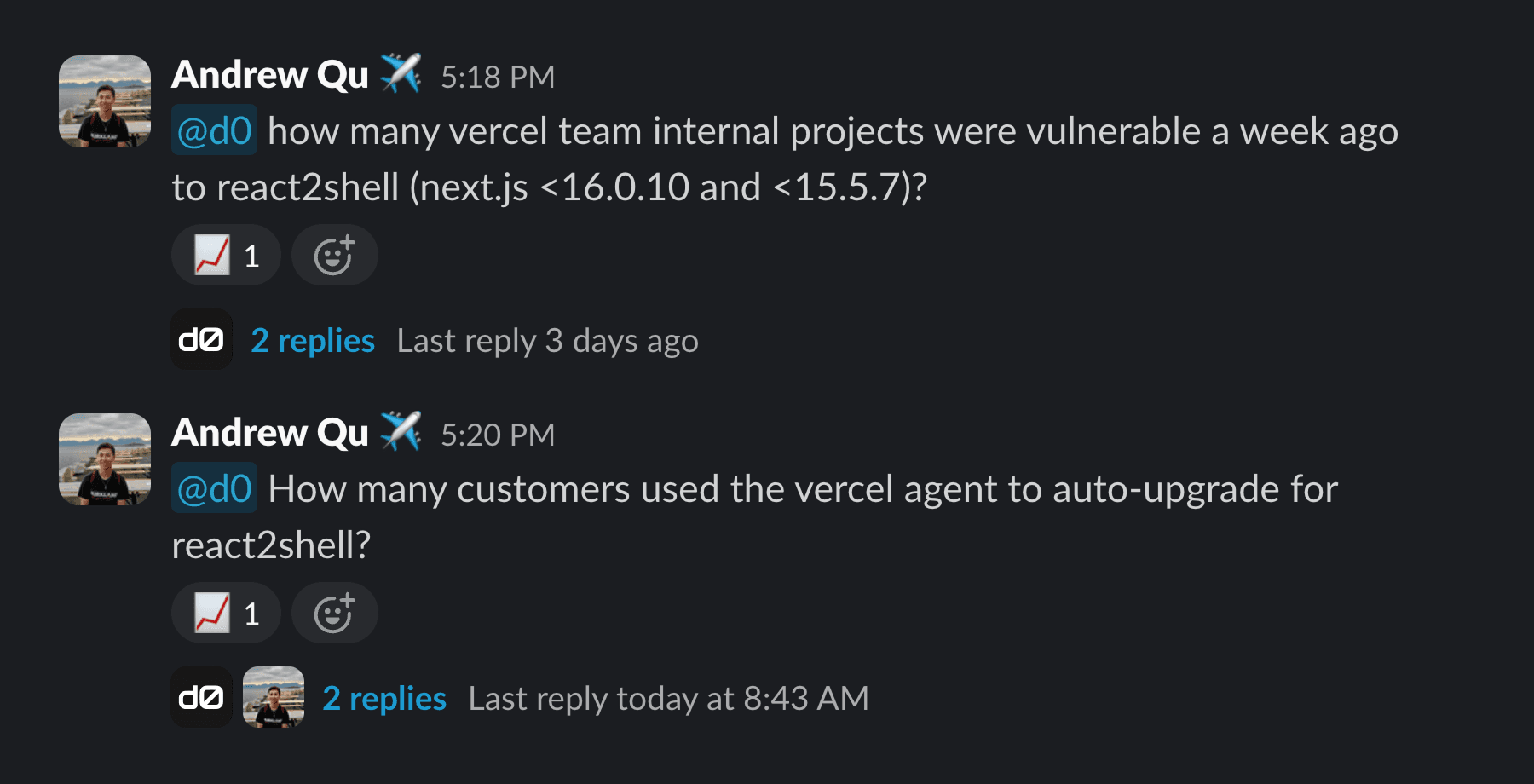

d0 translates natural language questions into SQL queries against our analytics infrastructure, letting anyone on the team get answers without writing code or waiting on the data team.

When d0 works well, it democratizes data access across the company. When it breaks, people lose trust and go back to pinging analysts in Slack. We need d0 to be fast, accurate, and reliable.

Link to headingGetting out of the model's way

Looking back, we were solving problems the model could handle on its own. We assumed it would get lost in complex schemas, make bad joins, or hallucinate table names. So we built guardrails. We pre-filtered context, constrained its options, and wrapped every interaction in validation logic. We were doing the model’s thinking for it:

Built multiple specialized tools (schema lookup, query validation, error recovery, etc.)

Added heavy prompt engineering to constrain reasoning

Utilized careful context management to avoid overwhelming the model

Wrote hand-coded retrieval to surface “relevant” schema information and dimensional attributes

Every edge case meant another patch, and every model update meant re-calibrating our constraints. We were spending more time maintaining the scaffolding than improving the agent.

import { ToolLoopAgent } from 'ai';import { GetEntityJoins, LoadCatalog, /*...*/ } from '@/lib/tools'const agent = new ToolLoopAgent({ model: "anthropic/claude-opus-4.5", instructions: "", tools: { GetEntityJoins, LoadCatalog, RecallContext, LoadEntityDetails, SearchCatalog, ClarifyIntent, SearchSchema, GenerateAnalysisPlan, FinalizeQueryPlan, FinalizeNoData, JoinPathFinder, SyntaxValidator, FinalizeBuild, ExecuteSQL, FormatResults, VisualizeData, ExplainResults },});Link to headingA new idea, what if we just… stopped?

We realized we were fighting gravity. Constraining the model’s reasoning. Summarizing information that it could read on its own. Building tools to protect it from complexity that it could handle.

So we stopped. The hypothesis was, what if we just give Claude access to the raw Cube DSL files and let it cook? What if bash is all you need? Models are getting smarter and context windows are getting larger, so maybe the best agent architecture is almost no architecture at all.

Link to headingv2: The file system is the agent

The new stack:

Model: Claude Opus 4.5 via the AI SDK

Execution: Vercel Sandbox for context exploration

Routing: Vercel Gateway for request handling and observability

Server: Next.js API route using Vercel Slack Bolt

Data layer: Cube semantic layer as a directory of YAML, Markdown, and JSON files

The file system agent now browses our semantic layer the way a human analyst would. It reads files, greps for patterns, builds mental models, and writes SQL using standard Unix tools like grep, cat, find, and ls.

This works because the semantic layer is already great documentation. The files contain dimension definitions, measure calculations, and join relationships. We were building tools to summarize what was already legible. Claude just needed access to read it directly.

import { Sandbox } from "@vercel/sandbox";import { files } from './semantic-catalog'import { tool, ToolLoopAgent } from "ai";import { ExecuteSQL } from "@/lib/tools";}

const sandbox = await Sandbox.create();await sandbox.writeFiles(files);

const executeCommandTool(sandbox: Sandbox) { return tool({ /* ... */ execute: async ({ command }) => { const result = await sandbox.exec(command); return { /* */ }; } })}

const agent = new ToolLoopAgent({ model: "anthropic/claude-opus-4.5", instructions: "", tools: { ExecuteCommand: executeCommandTool(sandbox), ExecuteSQL, },})Link to heading3.5x faster, 37% fewer tokens, 100% success rate

We benchmarked the old architecture against the new file system approach across 5 representative queries.

The file system agent won every comparison. The old architecture’s worst case took 724 seconds, 100 steps, and 145,463 tokens before failing. The file system agent completed the same query in 141 seconds with 19 steps and 67,483 tokens, and it actually succeeded.

The qualitative shift matters just as much. The agent catches edge cases we never anticipated and explains its reasoning in ways we can follow.

Link to headingLessons learned

Don’t fight gravity. File systems are an incredibly powerful abstraction. Grep is 50 years old and still does exactly what we need. We were building custom tools for what Unix already solves.

We were constraining reasoning because we didn’t trust the model to reason. With Opus 4.5, that constraint became a liability. The model makes better choices when we stop making choices for it.

This only worked because our semantic layer was already good documentation. The YAML files are well-structured, consistently named, and contain clear definitions. If your data layer is a mess of legacy naming conventions and undocumented joins, giving Claude raw file access won’t save you. You’ll just get faster bad queries.

Addition by subtraction is real. The best agents might be the ones with the fewest tools. Every tool is a choice you’re making for the model. Sometimes the model makes better choices.

Link to headingWhat this means for agent builders

The temptation is always to account for every possibility. Resist it. Start with the simplest possible architecture. Model + file system + goal. Add complexity only when you’ve proven it’s necessary.

But simple architecture isn’t enough on its own. The model needs good context to work with. Invest in documentation, clear naming, and well-structured data. That foundation matters more than clever tooling.

Models are improving faster than your tooling can keep up. Build for the model that you’ll have in six months, not for the one that you have today.

If you’re building agents, we’d love to hear what you’re learning.

Build an agent with Vercel and Slack

Start creating your own Slack Agent using the Bolt for JavaScript and Nitro template. Deploy it on Vercel to get a live, production-ready setup in minutes.

Deploy the template